Posted: May 26, 2013 in Dog Tails, Ginger the Fire Dog of Greenwich Village

Tags: 96 Charles Street, Columbian No. 14, fire dog, Hook and Ladder Company No. 5, Metropolitan Fire Department, New York History, Old New York

Tags: 96 Charles Street, Columbian No. 14, fire dog, Hook and Ladder Company No. 5, Metropolitan Fire Department, New York History, Old New York

0

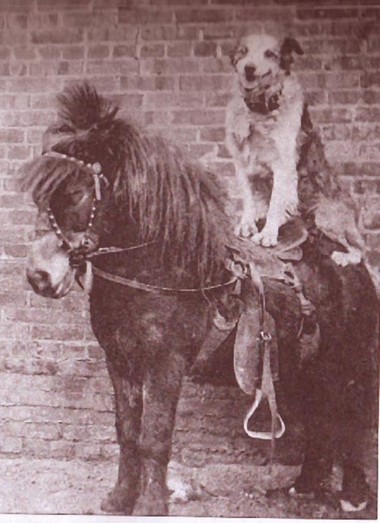

Although their names were omitted from the payrolls, the fire dogs of the Metropolitan Fire Department played some very important roles in nineteenth-century New York City. Not only were they considered pets of the firehouse and furry friends of the neighborhood, but they also worked hard barking loudly to clear the streets ahead of the horse-drawn engines, guarding the men’s equipment at the scene of a fire, spurring the horses on to greater speed by nipping at their legs, or alerting the firemen to injured fire victims.

For 16 years, Ginger did all of these things and more for Hook and Ladder Company No. 5 of Greenwich Village, New York.

Ginger, a mutt, joined the firehouse at 95 Charles Street in 1872 – just seven years after the hook and ladder company was organized. According to The New York Times, Ginger was a “fireman’s dog” who “took an almost human interest in the affairs of the company.” He would always promptly respond to fire alarms, and his short, sharp barks would mingle with the truck’s loud gong as he ran in front of the horses.

All the children in the neighborhood loved him, especially the little schoolgirls, who would often stop at the firehouse on their way to and from school to play with the friendly dog they called Ginger.

On November 16, 1888, Ginger met his demise while taking his daily walk on Bleecker Street. The old dog was reportedly injured when he was hit by a truck; a police officer used his revolver to put Ginger out of his misery. Ginger was buried in the yard of the firehouse following a visitation for the school children.

A Brief History of Hook and Ladder Company No. 5

The Metropolitan Hook and Ladder Company No. 5 was organized on September 25, 1865. It was one of the twelve hook and ladder companies organized that year under a state act titled “An Act to Create a Metropolitan Fire District.” This bill, passed into law on March 30, 1865, abolished New York’s volunteer fire department and created the Metropolitan Fire District, a Board of Commissioners, and the Metropolitan Fire Department (MFD).

The new hook and ladder company had 12 members, including Foreman Charles O’Shay, an assistant-foreman, driver, and nine privates. The combined annual salary for all the company members was $8,550.

In

1866, Harper’s Weekly featured this illustrated print celebrating the

official formation of New York City’s Metropolitan Fire Department.

Museum of the City of New York Collections

Mutual No. 1, Chelsea No. 2, Eagle No. 4, Union No. 5, Mechanics No. 7, Empire No. 8, Washington No. 9, C.V. Anderson No. 10, Harry Howard No. 11, Friendship No. 12, Columbian No. 14, Baxter No. 15, Liberty No. 16, Hibernia No. 18, Phoenix No. 3, Lafayette No. 6, Marion No. 13, John Decker No. 17.

During the transition, Columbian Hook and Ladder No. 14, which was housed at 96 Charles St., was replaced by Hook and Ladder Company No. 5. Hook and Ladder 5 occupied the Charles St. firehouse until November 25, 1975, when the company moved into its present quarters at 227 Sixth Avenue.

Columbian No. 14 — “Wide Awake”

This volunteer company was organized May 11, 1854, with Robert S. Dixon as foreman, Kinloch S. Derickson as assistant, Robert Wright as secretary, William Hutchings as treasurer, and ten other members. They worked out of a temporary location on Greenwich Street near Amos Street, which they erected at their own expense in May 1854. In January 1857 the company moved into their new Italianate-style firehouse on Charles Street and took possession of a new truck finished by Pine & Hartshorn of New York City.

On

April 21, 1860, Scientific American featured this illustration titled

“Fire escape Hook and Ladder Truck.” This apparatus is probably very

similar to the truck acquired by the Columbian No. 14 volunteer fire

company in 1857.

Built

in 1854 as a carriage house, 96 Charles Street was purchased by the

city in 1855 and converted to a firehouse for Columbian No. 14. Hook and

Ladder Company No. 5 occupied the firehouse from 1865 to 1975. Today

the building houses a contemporary art gallery and two large residential

duplexes.

In Memoriam

The following members from Ladder 5 and Battalion 2 made the supreme sacrifice on September 11th, 2001:

LADDER 5

Lt. Mike Warchola

Lt. Vincent Giamonna

Lou Arena

Andy Brunn

Greg Saucedo

Paul Keating

Tommy Hannafin

John Santore

BATTALION 2

BC. William McGovern

BC. Richard Prunty

FF. Fautino Apostol, Jr.

Pictured here are the 11 men of Ladder 5 and Batralion 2 who lost their lives at the World Trade Center on 9/11.